Artifacts

noun. /ahr-tuh-fakt/

An object remaining from a particular time or event.

Evidence of a system’s behavior that persists after the intent has faded.

Most industry writing focuses on how things are supposed to work. These files examine how they actually break. They are not tied to a calendar, because the tension between Capital and Capacity has no expiration date.

Why The Fix Is Known — And Still Not Chosen

The Invisible Wall

By the time most people reach this point, the question feels obvious.

If the risks are visible,

if the failure modes are understood,

if the incentives are misaligned but not mysterious,

then why doesn’t anything change?

The uncomfortable answer is this:

the fix is not missing.

It is simply not chosen.

The Myth of Ignorance

We often assume systems persist because decision-makers don’t understand them.

That assumption is comforting. It implies that insight alone could unlock change.

But in most operational systems, that isn’t true.

The mechanics are understood.

The trade-offs are named privately.

The technical debt is visible to those closest to it.

What’s absent is not awareness — it’s incentive alignment.

When Knowing Isn’t Enough

Most of the improvements that would stabilize the system are well known:

more accurate categorization instead of compressed averages

ranges instead of point estimates

capacity buffers instead of perpetual stretch

resilience designed into the system instead of extracted from people

None of this is exotic.

What is expensive is who pays for it — and when.

These fixes demand:

upfront cost

organizational humility

time horizons longer than most tenures

acceptance of lower short-term flexibility

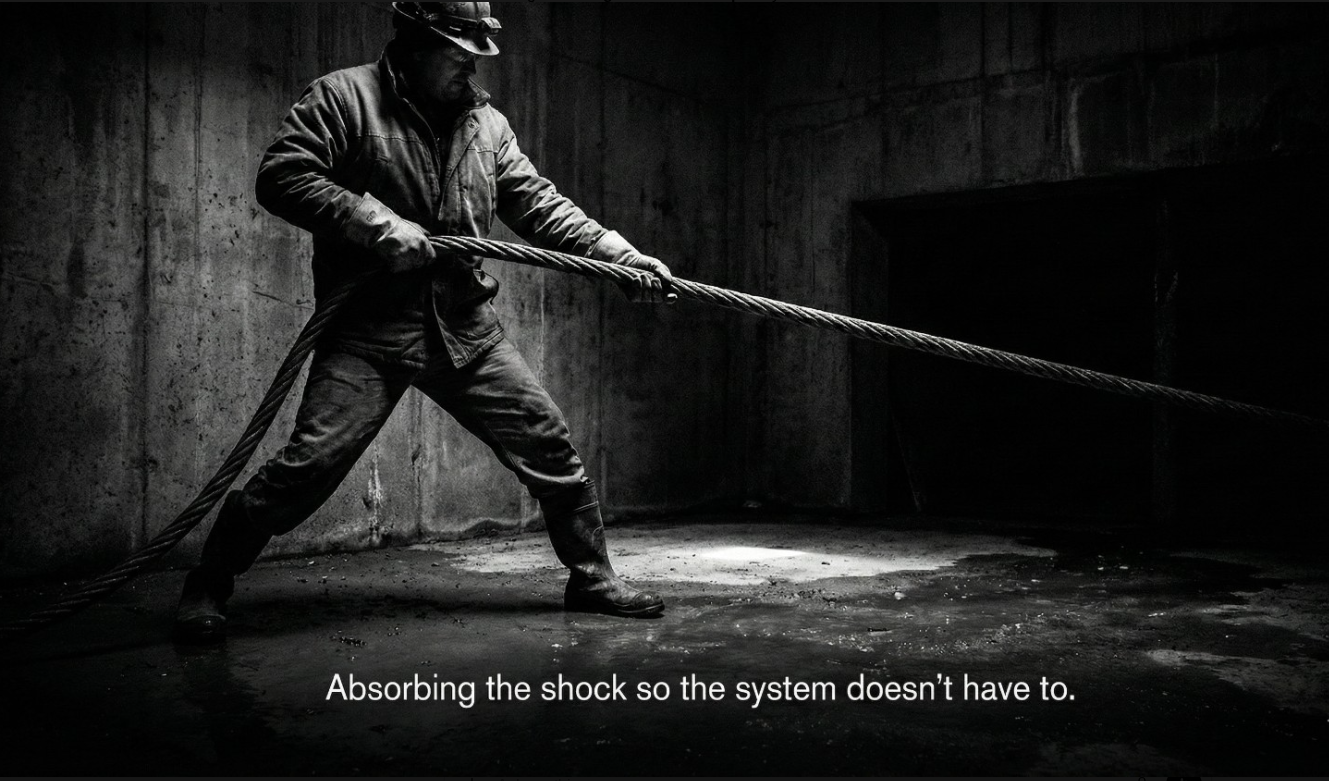

They require someone to absorb pain now so that others can benefit later.

That is rarely how power is structured.

The Asymmetry That Holds Everything in Place

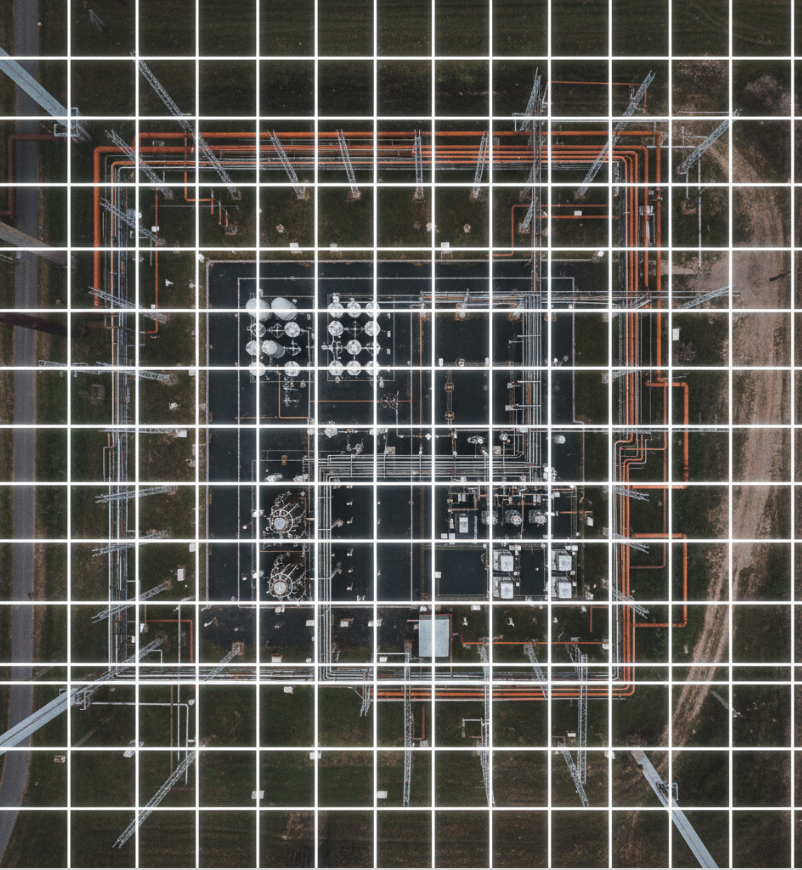

Today’s system functions because risk is displaced, not resolved.

Providers push variance downstream.

Vendors absorb uncertainty to stay alive.

Operators compensate with judgment and care.

As long as someone else is holding the load, the system appears to work.

Dashboards remain green.

Narratives remain intact.

Replacement remains easier than repair.

From a distance, endurance looks like health.

The Role of Time

Time is the quiet enforcer.

Leaders nearing the end of their tenure can often outrun the consequences of today’s decisions. Investors operating on fixed horizons are rewarded for extracting value before fragility surfaces. Vendors cannot pause to renegotiate the structure that feeds them.

Everyone is behaving rationally.

Just not collectively.

The system rewards those who move fastest — not those who make it last.

Why Change Rarely Comes Voluntarily

Meaningful reform doesn’t usually emerge from consensus or goodwill.

It emerges when the cost of not fixing the system finally exceeds the cost of doing so.

When vendor churn accelerates faster than replacement.

When judgment drains out faster than training can replace it.

When automation amplifies errors instead of smoothing them.

When the system can no longer hide where resilience was coming from.

Until then, the invisible wall holds.

This Is Not Cynicism

This isn’t an argument that people don’t care.

It’s an explanation of why caring isn’t enough.

The barrier isn’t intelligence or morality.

It’s incentive gravity.

Systems move in the direction they are rewarded to move — even when the destination is known to be wrong.

What Naming the Wall Does

Naming this dynamic doesn’t fix it.

But it does something quieter and more important.

It stops mistaking silence for ignorance.

It stops blaming individuals for structural outcomes.

It restores agency to those who understand the system but feel powerless to change it alone.

It reframes frustration as clarity.

And clarity is often the first thing a system needs — long before it is ready to act.

Where This Leaves Us

The fix has never been hidden.

It has simply been larger, slower, and more uncomfortable than the system was willing to choose.

For now.

Acceleration Without Understanding

The AI View

When systems strain, organizations reach for something superior.

A new leader with pristine credentials.

A new platform proven elsewhere.

A new framework that promises clarity where ambiguity has grown uncomfortable.

AI arrives into this exact pattern — the final and most powerful iteration of the borrowed playbook.

The Old Reflex, Upgraded

This instinct isn’t new.

When complexity overwhelms existing structures, the response has always been substitution:

replace judgment with authority

replace experience with process

replace ambiguity with certainty

AI simply upgrades the mechanism.

It doesn’t arrive as a suggestion.

It arrives as inevitability.

Because unlike previous interventions, AI doesn’t just support decision-making — it threatens to replace it.

What AI Actually Does

AI does not understand systems.

It recognizes patterns.

Those patterns are derived from historical data, encoded assumptions, and prior decisions — many of which were themselves shaped by incomplete models, mispriced resilience, and displaced risk.

This distinction matters.

AI doesn’t generate new judgment.

It amplifies the judgment already embedded in the system.

If the inputs reflect a healthy model, AI accelerates effectiveness.

If the inputs reflect a distorted one, AI accelerates failure.

Confidently.

Consistently.

At scale.

The Temptation to Predict Variance

In ops-heavy environments, the promise of AI is seductive.

If humans struggle with variance, perhaps models can predict it.

If judgment is inconsistent, perhaps algorithms can normalize it.

If forecasting fails, perhaps more data will make it precise.

But this misunderstands the problem.

Variance is not a data deficiency.

It is a property of the physical world.

Trying to predict every raindrop doesn’t remove the rain.

It just distracts from building better umbrellas.

When Escape Hatches Disappear

Historically, systems survived their own flaws because humans compensated.

Operators adjusted.

Vendors improvised.

Leaders exercised discretion.

These were escape hatches.

They were informal, imperfect, and unscalable — but they allowed the system to bend rather than break.

AI removes those escape hatches.

Decisions become algorithmic, not discretionary.

Failures become systemic, not local.

Responses become acceleration, not reflection.

When the model fails, it fails everywhere at once.

Judgment Is a Use-It-or-Lose-It Capability

There is a deeper cost that rarely appears in business cases.

Judgment atrophies.

When technicians defer to prompts instead of principles, the organization slowly loses its operational brain. Skills that once lived in people are externalized into systems that cannot improvise when reality deviates — which it always does.

When the system finally fails, there is no one left who knows how to fix it without a screen.

That is not efficiency.

That is fragility with confidence.

The Illusion of Objectivity

AI feels neutral.

It doesn’t argue.

It doesn’t tire.

It doesn’t escalate emotionally.

This makes its outputs feel authoritative — even when they are wrong.

And because AI reflects institutional assumptions back to leadership with mathematical certainty, it becomes harder to question the model than to question the people it replaces.

The organization doesn’t become smarter.

It becomes more convinced.

What AI Cannot Fix

AI cannot repair misaligned incentives.

It cannot lengthen time horizons.

It cannot price resilience correctly.

It can only operate within the system it is given.

And if that system was already extracting resilience from people, AI will simply do it faster.

The Real Choice

The question is not whether AI belongs in operations.

It does.

The question is whether organizations are willing to understand the system — its time constants, its human buffers, its irreducible variance — before asking a tool to make it run faster.

Acceleration without understanding doesn’t solve fragility.

It completes it.

Where This Leaves Us

AI is not the villain.

It is the mirror.

It reflects the system’s assumptions back at scale — with speed, confidence, and no regard for consequence.

Whether it becomes a force for resilience or collapse depends entirely on what the system brings to it.

That choice is still open.

For now.

When The Playbook Breaks

The Process View

When systems begin to strain, organizations do the responsible thing.

They bring in experts.

Consultants arrive with experience from environments where scale is clean, variance is bounded, and outcomes can be normalized. Frameworks are introduced. Playbooks are borrowed. Processes are standardized.

None of this is foolish.

It is rational.

And it often works — just not here.

The Appeal of the Borrowed Playbook

Most modern process frameworks were forged in industries where work is:

digital

repeatable

reversible

statistically stable

In those environments, averages are meaningful. Variance is noise. Optimization is additive.

Operations-heavy industries look similar from a distance. Work can be categorized. Costs can be averaged. Performance can be benchmarked.

So the instinct is natural:

compress the system into something legible.

Where Reality Refuses Compression

In physical operations, variance is not noise.

It is the work.

Consider three jobs that appear identical on paper: replacing a 300-foot damaged fiber segment.

One is aerial — straightforward, two bucket trucks, minimal disruption.

One is buried in dirt — trenching, locates, permits, traffic control.

One is under asphalt with rock — boring, rock adders, restoration, staging, and risk.

From a spreadsheet perspective, these are the same unit.

From reality’s perspective, they are different species.

Costs range from thousands to tens of thousands.

Timelines diverge.

Risk profiles explode.

The average doesn’t describe the work — it describes a scenario that does not exist.

The Seduction of Precision

Faced with this variance, organizations don’t retreat from modeling.

They double down.

More software.

More fields.

More categories.

More enforcement.

The goal becomes precision.

But precision is not the same as accuracy.

When tools demand a single point instead of a range, the system is forced to lie — politely, consistently, and with confidence.

A buried segment in dirt is predictable.

A rock vein is not.

To the process, that’s a variance request.

To the P&L, it’s a structural break.

Vendors Feel This First

Nowhere is this tension felt more acutely than on the vendor side.

In the build phase, forecasting is easier. Quantities are known. Footage is planned. Resources can be staged.

Operations are different.

Vendors are asked to price work without guaranteed volume, while carrying fixed costs for equipment, labor, insurance, and compliance.

Price too high, and you lose the work.

Price too low, and you subsidize it.

Meanwhile, providers — facing their own margin pressure — push rates down further, assuming efficiency can compensate for uncertainty.

Nothing about the physics changes.

Only who absorbs the variance.

When Judgment Becomes the Liability

As process rigidity increases, something else quietly shifts.

Judgment is replaced with compliance.

Ranges are replaced with targets.

Experience is replaced with enforcement.

This isn’t just an efficiency move — it’s a trust signal.

When we replace judgment with metrics, we aren’t simply improving accountability.

We are signaling that we no longer trust the person closest to the work.

That trust debt compounds.

Judgment is a use-it-or-lose-it capability.

When it atrophies, the system loses its ability to respond when reality deviates — which it always does.

When failure finally arrives, no one knows how to fix it without a screen.

Why the Playbook Breaks

The playbook doesn’t fail because it’s poorly designed.

It fails because it assumes homogeneity in a system defined by variance.

It assumes reversibility in a system where mistakes harden into concrete and asphalt.

It assumes optimization is local when costs propagate nonlinearly.

And it assumes that what worked elsewhere will work again — if only enforced tightly enough.

At that point, process stops serving the system.

The system starts serving the process.

What Actually Breaks

The system doesn’t collapse when a model is wrong.

It collapses when everyone knows the model is wrong — and continues to use it anyway.

Trust erodes.

Vendors churn.

Operators disengage.

Margins thin.

Not because people are incompetent — but because the framework cannot hold the work it is being asked to describe.

This is not a failure of execution.

It is a failure of fit.

The Setup for Acceleration

When process fails, the instinct is not reflection.

It is acceleration.

If humans can’t manage the variance, perhaps machines can.

If judgment is unreliable, perhaps prediction can replace it.

That belief sets the stage for the next act.

What The Broadband Industry Misunderstood About Itself

The Capital and Industry View

The broadband industry did not fail in the way failure is usually measured.

Coverage expanded. Speeds increased dramatically. Capital flowed. Millions of households gained access to infrastructure that did not exist a decade earlier. By any build-phase metric, broadband was a success.

That is not the failure this essay examines.

The failure was subtler — and only becomes visible once the industry crossed from building infrastructure to operating essential systems.

What broadband misunderstood about itself was not how to deploy fiber, attract capital, or compete on speed. It misunderstood the kind of system it was becoming once expansion slowed and durability mattered more than velocity.

The industry succeeded at construction.

It struggled with transition.

Speed Was Rational — and Still Incomplete

In its growth phase, broadband optimized relentlessly for speed.

This was not recklessness. It was necessity.

Competition intensified. Capital flowed. New entrants emerged. Differentiation moved quickly from availability to bandwidth, from bundles to gigabit promises. Deployment velocity became existential.

Incumbents raced to defend territory. New providers raced to claim it. Middle-mile operators formed. Vendors scaled. The system expanded at full throttle.

In that moment, speed was not a mistake.

It was the only move that made sense.

But optimization always comes with a trade.

What broadband optimized for was deployment velocity, not operational durability.

The cost of that trade was deferred.

Early Builders Paid the Pioneer Penalty

The first wave of builders paid for learning at scale.

They invested in architectures, tooling, labor models, and training programs based on the best information available at the time. Engineering assumptions hardened into standards. Field practices became institutionalized.

Years later, manufacturers simplified deployment through pre-connectorized fiber, modularized components, and reduced the need for labor-intensive splicing that incumbents had already built entire organizations around.

The industry became more efficient — but not uniformly.

New entrants inherited cheaper, simpler deployment models. Early builders carried sunk costs that could not be unwound without disrupting live systems.

The market did not reward experience.

It rewarded timing.

Infrastructure Is a Long Game — Capital Often Is Not

Broadband is fundamentally a long-lived asset.

Fiber plants are designed to last decades. Returns accrue slowly. Value is realized through durability, not velocity.

But much of the capital flowing into the industry operated on a very different clock.

Three- to five-year horizons. Quarterly narratives. EBITDA projections that assumed operational stability as a given rather than a design requirement.

This created a structural mismatch.

A 30-year asset was being managed under short-money expectations.

Not because investors were malicious — but because their tools, incentives, and pattern libraries were built for industries where variability is lower and reversibility is higher.

Broadband is neither.

Operations Was Treated as Elastic

As the build phase tapered and the industry shifted into operations and maintenance, something subtle happened.

Operational resilience was assumed to be flexible.

Costs could be squeezed. Vendors could be rotated. Teams could be leaned out. Judgment could be standardized.

Margins tightened, but dashboards stayed green — for a while.

What those dashboards could not show was where the resilience was coming from.

It was not embedded in the system.

It was embedded in people.

Operators absorbed ambiguity. Vendors stretched capacity. Tribal knowledge filled gaps the models did not capture.

Resilience was not designed.

It was extracted.

The Convergence Problem

The system did not fail abruptly.

Multiple stabilizers were eroding at different rates:

workforce experience thinning

vendor margins compressing

maintenance backlogs growing

capital expectations hardening

Each erosion felt survivable in isolation.

The miscalculation was assuming they would not converge.

But systems do not fail when one leg weakens.

They fail when enough legs weaken at once.

At that point, the chair cannot stand — not because everything collapsed, but because too much erosion aligned.

The industry did not run out of intelligence.

It ran out of slack.

Mispriced Resilience

Resilience was priced — just not correctly.

Leaders believed they had more time.

They believed erosion would remain staggered.

They believed experience could be transferred, standardized, or replaced.

What they underestimated was that tribal knowledge is not a scalable asset.

It does not transfer cleanly.

It does not appear on balance sheets.

And once lost, it does not regenerate on demand.

Elasticity only works when systems are allowed to recover.

Held under constant tension, it becomes brittle.

What Was Actually Misunderstood

The broadband industry misunderstood one core truth about itself:

It is not a speed business.

It is a durability business that requires speed upfront.

Those are not the same thing.

When durability is treated as free, it eventually becomes scarce.

When resilience is extracted instead of designed, it eventually disappears.

The result is not collapse.

It is fragility disguised as performance.

This Is Not an Anomaly

What we are seeing now is not a surprise.

It is the system behaving exactly as it was built to behave once the conditions changed.

The next phase will test something deeper:

whether borrowed processes, borrowed capital models, and borrowed acceleration tools can function in a system defined by physical reality, irreducible variance, and long time constants.

That question is still unfolding.

The Silence Between Signals

The Leadership View

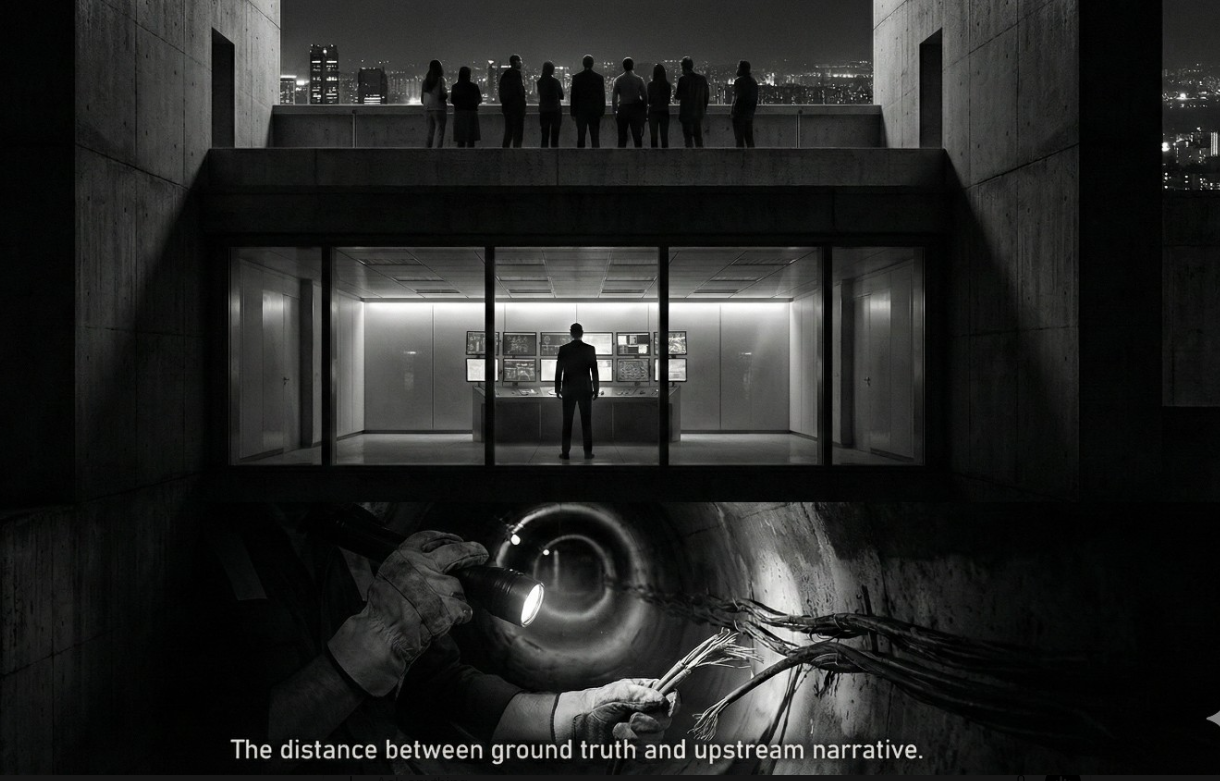

From the leadership seat, the story looks different.

The warnings don’t arrive cleanly or in isolation. They arrive amid budget reviews, headcount constraints, board expectations, and an endless stream of competing priorities—each one urgent, each one defensible.

Every day brings more signals than any individual or team can fully absorb.

Most leaders are not ignoring risk.

They are prioritizing under constraint.

And that distinction matters.

The Signal-to-Noise Problem

As organizations scale, leaders stop receiving information as events and start receiving it as patterns.

Individual risks blur together. Each escalation competes with dozens of others. Everything feels important, which paradoxically makes it harder to act on anything decisively.

From this vantage point, deferral feels rational.

“We’ll revisit next quarter” isn’t dismissal.

It’s triage.

But triage assumes something critical:

that the system can safely hold what has been deferred.

That assumption is rarely examined.

When Decisions Are Made Quietly

In many cases, leadership does make a decision.

Capital is allocated elsewhere.

Resources are directed toward higher-visibility initiatives.

A calculated bet is placed that the system can tolerate degradation for a while longer.

What’s missing is not intent—but articulation.

Risk acceptance often remains implicit. The time horizon is undefined. The tolerance threshold is unspoken. And the ownership of consequence remains ambiguous.

From the leadership seat, the decision feels settled.

From the operator’s seat, it feels like nothing was decided at all.

That gap is not a communication failure.

It’s a structural one.

Narrative Pressure and Time Compression

Leadership operates under a different kind of load.

Dashboards roll up. Board decks flatten nuance. Performance is measured in quarters, not conditions. Explanations must fit into slides, not field reports.

This creates narrative pressure.

Green metrics become proxies for health. Variance becomes something to “manage,” not something to sit with. Ambiguity becomes a liability.

Under this pressure, leaders don’t eliminate risk.

They compress it.

And compression favors what can be reported over what can be felt.

The Illusion of Control

The danger isn’t that leaders are cynical.

It’s that the system rewards confidence.

When something goes wrong, the question isn’t “what did we assume?”

It’s “why didn’t this get escalated harder?”

This reframing subtly shifts accountability downward.

Risk that was consciously tolerated becomes failure that was insufficiently prevented. And because the original decision was never named, the system has no memory of having chosen the outcome.

This is how leadership feels blindsided by events they implicitly approved.

Where Trust Quietly Erodes

Trust doesn’t break when trade-offs are made.

It breaks when trade-offs are invisible.

When operators aren’t told that a risk has been accepted, they continue to carry it personally. They compensate. They absorb. They stay vigilant.

Over time, this creates asymmetry.

Leadership believes the system is holding.

Operators know exactly who is holding it.

When failure eventually surfaces, both sides feel wronged—and both are, in different ways.

What Leadership Actually Owes the System

Leadership responsibility is often framed as decisiveness.

But in ops-heavy systems, clarity matters more than certainty.

Naming a decision—even an uncomfortable one—preserves alignment:

We see the risk.

We’re choosing to tolerate it for now.

Here’s the window.

Here’s what would change the decision.

Here’s who owns the outcome.

This doesn’t remove risk.

It relocates it consciously.

And that distinction is the difference between resilience and quiet erosion.

Why This Matters

When decisions remain implicit, systems lose their early warning signals.

Escalation becomes performative.

Silence becomes rational.

Competence withdraws—not out of apathy, but out of self-preservation.

Leadership doesn’t fail because it lacks intelligence or intent.

It fails when it allows risk to be carried without being acknowledged.

Resilience doesn’t come from better dashboards.

It comes from decisions the system can see.

Risk Was Taken - Just Not Where You Thought

Part 1 (Operators View)

There’s a moment most competent operators recognize instantly.

You raise a concern early.

Not dramatically.

Not emotionally.

Just clearly.

Something is degrading.

A dependency is brittle.

Preventive work is being deferred past the point where it still feels responsible.

Leadership listens.

They nod.

They offer False Alignment—the kind of supportive listening that feels like agreement but results in no change of state.

Then they say some version of: “Let’s table that for now.” “We’ll revisit next quarter.”

On the surface, nothing seems wrong.

No argument.

No dismissal.

But something subtle breaks anyway.

The Burden of Lived Risk

By "operators," I mean the people accountable for system health and execution. Titles vary—from Senior Engineers to VPs of Operations—but the position in the system does not.

Competent operators are trained to sense drift before it becomes failure. They escalate, not because they enjoy friction, but because silence feels irresponsible.

When a real risk is raised and the response is deferral without context, the mind fills in the gaps:

This doesn’t matter.

My judgment isn’t trusted.

I am overreacting.

From the operator’s seat, the risk hasn't been "tabled." It has been orphaned. There is no timeline, no threshold, and no shift in ownership. The organization accepts the risk on paper; the operator accepts the risk in their sleep.

The Moral Hazard of Silence

In many cases, a decision has been made. Trade-offs were evaluated. Resources were allocated elsewhere. The risk was acknowledged and "priced" by leadership. But the decision remains hidden behind Strategic Ambiguity.

No one says whether the risk was being accepted.

No one says for how long.

No one says under what conditions it would be revisited.

Most importantly, no one says whether you are still expected to prevent the failure with the same limited constraints.

This creates a massive Moral Hazard.

The organization takes the "upside" of moving resources to other projects, while the operator carries the "downside" of the looming failure.

It is Accountability without Authority.

The Corrosive Moment

Operators don’t escalate for effect.

They escalate because unresolved risk feels personal.

Because they know exactly who will be asked for an explanation when the system eventually fails.

When escalation meets a polite nod, something changes quietly.

You keep delivering.

You keep compensating.

But you stop investing the same emotional energy.

Caring without agency is unsustainable.

Months later, the failure arrives. The questions follow quickly:

“Why wasn’t this prevented?”

“Why didn’t this get escalated harder?”

“Why didn’t anyone say something?”

This is the most corrosive moment.

Because you did say something.

Early. Clearly. More than once.

What you weren’t told was that the organization had already chosen to live with the risk.

That ownership had shifted upward the moment you spoke.

That prevention was no longer expected within the current trade-offs.

Where Trust Fractures

The damage isn’t that risk was taken.

Risk-taking is inevitable in any real organization.

The damage is simpler and quieter.

Risk was accepted at the top, while the consequences remained downstream.

When that pattern repeats, escalation starts to feel pointless.

Silence starts to feel rational.

Competence withdraws—not loudly, but reliably.

From the operator’s side, the experience isn’t: “Leadership made a bad call.”

It’s this: “I don’t know what decision exists—but I’m still carrying the weight of it.”

That gap is where the signal dies.

Next Step: In Part II, we’ll look at this same dynamic from the leadership seat. We’ll explore the "Signal-to-Noise" problem and why what looks like a clear warning to an operator often sounds like "background static" to a leader managing a thousand different fires.

When Silence Scales

The Ceiling You Can’t Outperform (Pt 3)

Systems rarely fail at the moment risk is introduced.

They fail later —

after the conditions have stabilized,

after the dashboards look calm,

after the experts have gone quiet.

This is not a leadership problem.

It is not a culture problem.

It is not a talent problem.

It is a signal problem.

Silence Is Commonly Misread

In mature organizations, silence is often interpreted as health.

Fewer escalations.

Cleaner handoffs.

Stable metrics.

Predictable delivery.

From the system’s perspective, these are signs of progress.

Noise has been reduced.

Variation has been constrained.

Outcomes appear controlled.

What the system does not see is why the noise disappeared.

Silence is not always alignment.

Sometimes it is withdrawal.

How Risk Accumulates Quietly

Risk does not arrive as an event.

It accumulates as absence.

The absence of:

Early warnings

Informal dissent

“This doesn’t feel right” conversations

Edge-case intuition that never makes it into documentation

When competence is extracted into artifacts, what remains looks complete.

Runbooks exist.

Playbooks are current.

Processes are documented.

The system feels confident.

But judgment does not scale the same way documentation does.

And judgment is usually the first thing to go quiet.

The Illusion of Stability

This is the most misleading phase.

After experienced operators disengage or exit, nothing breaks immediately.

In fact, things often look better:

Fewer interruptions

Faster throughput

Cleaner metrics

The system interprets this as validation.

“See?”

“We’re fine.”

What’s actually happening is simpler.

The system is still running on momentum.

Most systems fail not when expertise leaves, but when an unanticipated condition appears and no one recognizes it early enough to intervene.

That delay is the danger.

Lag Is the Game

Organizations rely on lagging indicators because they are measurable.

Availability.

Throughput.

Cost.

Cycle time.

These metrics confirm that the past behaved as expected.

They say very little about whether the system is still capable of sensing what comes next.

This is how risk survives leadership transitions, reorganizations, and executive exits.

The consequences are real — just not immediate.

So narratives hold.

Promotions are awarded.

Success is claimed.

Exits look clean.

By the time fragility surfaces, the people who could have named it earlier are no longer in the room.

When Silence Becomes Infrastructure

At scale, silence stops being an individual choice.

It becomes a property of the system.

Fewer people raise concerns because:

It doesn’t change outcomes

It increases exposure

It slows delivery without authority

Over time, the organization trains itself to operate without early signals.

This is not apathy.

It is optimization.

The system has learned that quiet competence is safer than visible judgment.

Until it isn’t.

The Postmortem Pattern

Every system failure eventually asks the same question:

“Why didn’t anyone catch this earlier?”

The answer is almost never:

“No one knew.”

It is:

“Someone knew, but stopped saying it.”

Not out of malice.

Not out of laziness.

But because the system no longer made space for that signal.

This Is the Cost of Extracted Competence

The danger is not that people leave.

The danger is that the system learns to function as if no one ever will.

By the time leadership realizes something is missing, the loss has already compounded.

Not in metrics.

In foresight.

Not in output.

In resilience.

And by then, silence is no longer a symptom.

It is infrastructure.

Closing

Systems do not collapse when experts exit.

They collapse when they stop hearing what expertise sounds like.

By the time silence becomes visible, it has already scaled.

The Fear of Being Too Competent

The Chef vs The Recipe (The Ceiling You Can’t Outperform pt. 2)

The Fear of Being Too Competent

Once you see the ceiling, something subtle changes.

Not in how you work.

But in how the work feels.

What once felt like momentum begins to feel like containment. The competence you took pride in starts to register differently — not because it lost value, but because of how that value is now being used.

This is where fear enters the system.

When Competence Stops Feeling Safe

Before the ceiling, competence feels protective.

You solve hard problems.

You earn trust.

You become indispensable.

After the ceiling, competence takes on a second meaning.

You begin to notice that:

The more you know, the more dependent the system becomes on you

The more you fix, the more work quietly routes your way

The more stable things get, the less visible your contribution becomes

Your expertise is no longer building leverage.

It is building dependency.

And dependency is not rewarded the same way growth is.

The System Wants the Recipe

In operations, product, and delivery environments, competence eventually produces artifacts.

Playbooks.

Runbooks.

Process maps.

Tribal knowledge made explicit.

This is not sinister.

It is how systems scale.

The organization wants the recipe so it doesn’t have to rely on the chef.

Repeatability reduces risk.

Documentation lowers cost.

Knowledge capture improves resilience.

But for the individual, something changes the moment the work becomes fully transferable.

You begin to ask:

If everything I know is written down, what exactly is my leverage now?

If my judgment has been turned into process, what differentiates me?

Am I being developed — or converted into infrastructure?

These are not paranoid questions.

They are rational ones.

Why the Fear Stays Quiet

This fear is rarely spoken aloud.

Because naming it carries risk.

Not just the risk of sounding:

Ungrateful

Insecure

Political

But something more final.

Redundant.

To articulate this fear is to acknowledge that your value may have peaked — that you have reached the point where your role is operationally essential but no longer strategically expanding.

And once that possibility is named, it cannot be unheard.

So most people don’t name it.

They keep delivering.

They keep stabilizing.

They keep absorbing complexity.

Outwardly, nothing changes.

Internally, the relationship with work does.

When Silence Becomes Armor

After the ceiling, the usual mechanisms stop working.

Advocacy doesn’t expand authority.

Transparency doesn’t increase protection.

Performance doesn’t move outcomes.

At that point, silence becomes the only available armor.

Not disengagement — preservation.

This is the missing link between fear and behavior.

When growth is capped and exposure increases, restraint becomes rational.

Strategic Preservation (What Others Call “Quiet Quitting”)

At this stage, many high performers make a quiet, disciplined adjustment.

They don’t stop caring.

They stop over-investing.

They become more selective about what they fix.

They document with intention, not enthusiasm.

They say “that’s outside scope” without apology.

What gets labeled as “quiet quitting” is often something else entirely.

It is strategic preservation by people who have learned that competence without mobility is containment.

Not laziness.

Not resentment.

Adaptation.

This Is Not a Failure of Character

It’s important to be precise.

This shift is not entitlement.

It is not disengagement.

It is not a lack of resilience.

It is the rational response of professionals who have recognized that the system rewards utility more reliably than development.

Once you see that, pretending otherwise doesn’t make you principled.

It makes you exposed.

Where This Leads Next

Seeing the ceiling explained stagnation.

Feeling the fear explains withdrawal.

But there is a third order effect — one organizations are far less prepared to confront.

What happens when the people who understand the system best stop volunteering that understanding?

What happens when silence scales?

That’s the next conversation.

The Ceiling You Can’t Outperform

For professionals in roles where execution is critical, performance is supposed to be legible.

Deliver results.

Remove friction.

Stabilize the system.

Get recognized accordingly.

That belief usually holds — until it doesn’t.

Sam Didn’t Guess

By Q3, Sam knew he was outperforming expectations.

The previous year, his results had been solid but unremarkable, and the raise reflected that. This year was different. Friction points that had lingered for years were resolved. Entire workflows were simplified. The organization avoided more than $6M in downstream cost.

There was no ambiguity in the signal.

He watched the CFO publicly applaud his department for outstanding performance. He received consistent reinforcement from leadership that his work mattered, that it was noticed, that it made a difference.

So when review season arrived, Sam didn’t speculate.

He expected alignment.

What he received instead was familiarity.

The same performance band.

The same compensation outcome.

A raise that existed mostly in words.

The praise was generous.

The outcome was identical.

This Is Where the Ceiling Appears

Moments like this are often misread.

Not as a system constraint, but as:

A communication failure

A negotiation miss

A one-off disappointment

But what Sam encountered was not a judgment on his contribution.

It was a ceiling.

A point where performance stopped compounding — not because it declined, but because it had become assumed.

Performance Is Not the Negotiating Currency

Organizations do not reward performance in isolation. They reward based on perceived risk.

Who might leave.

Who is hard to replace.

Who introduces uncertainty if underpaid.

Reliability reduces perceived risk.

And when perceived risk drops, compensation pressure drops with it.

This creates a quiet paradox:

The more effectively you stabilize the system, the less urgent it feels to materially change your outcome.

Why Execution Roles Hit This First

In execution-heavy roles, success removes evidence.

In operations, silence is the ultimate KPI —

but silence doesn’t demand a budget increase.

When things work:

There is less noise

Less escalation

Less visibility

Complexity is absorbed, not showcased.

Outages avoided don’t trend.

Crises prevented don’t headline.

Stability doesn’t argue for itself.

Over time, exceptional delivery becomes baseline expectation. The work still matters — but it no longer moves the needle.

Not because it lacks value, but because it lacks threat.

The Ceiling Is Structural, Not Personal

The ceiling is often internalized as a personal shortcoming:

“I should have done more.”

“I should have advocated harder.”

“Next cycle will be different.”

But the ceiling is not about effort.

It is about utility.

It is the moment your role becomes operationally essential but strategically safe.

At that point, performance alone has exhausted its leverage.

The system isn’t broken. It is working exactly as intended.

It has identified a high-functioning component and optimized for stability at minimal cost.

Seeing the Ceiling Changes the Rules

Once you see the ceiling, the corporate landscape gains depth.

Patterns that once felt like bad luck sharpen into structure.

You begin to understand:

Why raises flatten while responsibilities expand

Why recognition becomes purely verbal

Why contribution and outcome slowly separate until they no longer share the same conversation

This is not the end of the story —

but it is the point where the high-achiever identity begins to fracture.

The competence that built your career no longer compounds.

It contains.

And it is here that a new emotion emerges.

Not confusion.

Fear.

Fear of being too competent to promote.

Fear of becoming extractive infrastructure — a resource to be mined rather than a capability to be developed.

Fear of being truly invaluable, right up until the moment you aren’t.

That’s where the next conversation begins.

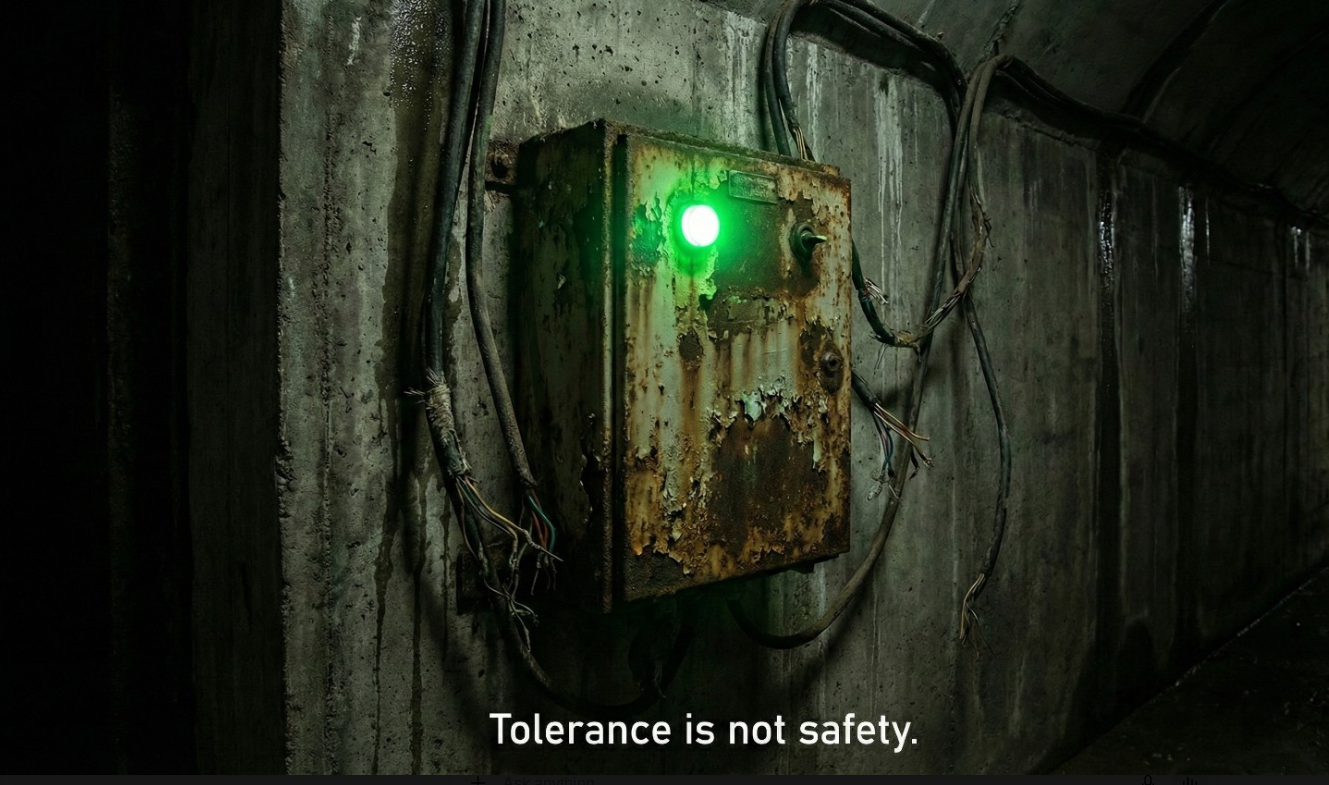

Green Is Not Health

Dashboards were built to give us distance.

A way to step back from complexity and see the system as a whole. A way to summarize what was happening without having to be everywhere at once. Somewhere along the way, that summary became an authority. And without anyone explicitly deciding it, green stopped meaning “within tolerance” and started meaning “safe.”

Operations teams know this is a lie.

Not a malicious one. A convenient one.

The NOC knows it. Field techs know it. Most experienced ops managers know it. Yet we still celebrate green dashboards as if they were proof of health rather than evidence of survival.

The NOC, to be fair, has an impossible job. They work with abstractions layered on abstractions: telemetry delayed by minutes, signals filtered through thresholds, projections built on incomplete visibility. Their margin of error is necessarily wide. It has to be. The system demands certainty anyway.

So we accept the projection.

Green feels good because it allows thinking to stop. It is easy to repeat. Easy to forward. Easy to quote in meetings. Nobody asks how green something is, because the dashboard already answered the question we were willing to ask.

Reality, unfortunately, is not obligated to cooperate.

There are moments in operations where reality is physically present—where a tech is standing over a splice that is barely holding together, where continuity tests confirm signal, where OTDRs show degradation that has been screaming quietly for months. And yet none of this counts until the dashboard agrees.

We wait for permission from the abstraction.

It’s like taking a picture with a broken camera and concluding that because the image didn’t come out, the subject must not exist. The evidence is there, but it doesn’t register in the system we’ve decided to trust.

This is where the tension becomes visible.

Executives quote dashboard health status while operations argues from the field. Not because anyone is dishonest, but because the executive vantage point is binary by necessity. They are not going to pop handholes. They are not going to interpret fiber test results. They require a signal that scales. Green or red. Up or down. This is not a conflict of value. It’s a conflict of signal resolution.

The tragedy is not that they trust dashboards.

It’s that we gave them nothing else that could travel upward without distortion.

Green, in practice, often means tolerance—not health.

A 24-count cable serving six homes can lose margin quietly. Spares get consumed. Repairs get shortcut. Working pairs get reassigned.

The dashboard stays green—not because the plant is healthy, but because it hasn’t yet exhausted what little tolerance remains.

But what’s actually happening is accumulation.

Latent failure. Deferred work. Capacity being quietly consumed until the final fiber breaks—after months or years of warning that nobody was incentivized to stop and address. When that day comes, the repair is no longer minor. It’s invasive, expensive, and disruptive.

And now the same operations teams who flagged the risk early are forced to explain why fixing a single customer requires rebuilding an entire lateral.

Welcome back to the myth of later.

The dashboard didn’t lie.

It simply told a smaller truth than we pretended it did.

Green was never supposed to mean safe. It meant within tolerance. But tolerance is a moving boundary, and systems degrade long before they fail. Most organizations only learn this when the abstraction finally turns red—long after the cost of intervention has multiplied.

Everyone in operations knows this.

Green is not health.

It is permission to look away.

And the longer we treat summaries as sources of truth, the more often reality will have to argue for its own existence.

Everyone Has Ideas. Operations Pays for the Wrong Ones

It All Begins Here

Most organizations celebrate the moment something launches.

The decks.

The demos.

The applause.

But very few spend equal time considering what happens the day after.

Deliverables are handed off.

Roadmaps move forward.

And Operations inherits responsibility.

This is not a failure of design or leadership. It is the natural result of how pressure is distributed inside most organizations.

Build teams operate under real constraints. They are expected to innovate, hit timelines, and protect margins. Decisions are made under urgency, not negligence. When quality is deferred, it is rarely ignored — it is scheduled for later.

Executives operate under a different, equally real pressure. They are accountable for market performance, organizational survival, and the livelihoods attached to both. They balance risk not out of indifference, but necessity. Delaying a launch has consequences just as real as shipping something imperfect.

These pressures converge at one place.

Operations.

Operations has no roadmap horizon and no “later.” Its mandate is singular: keep the system running.

When deferred quality surfaces — as performance issues, outages, or edge-case failures — Operations is already inside the blast radius. Customers are affected. Revenue is exposed. Time disappears. Empathy is not absent, but irrelevant. The system is live.

This is where abstraction ends.

What was once a design trade-off becomes a ticket.

What was once an assumption becomes an outage.

What was once a shortcut becomes a 2 a.m. call.

A system may launch without full redundancy to meet a market window. The risk is acknowledged and documented. But when demand scales faster than expected, it is Operations managing load, stabilizing behavior, and answering for decisions made months earlier — with no authority to reverse them in the moment.

This pattern repeats across industries. The specifics change, but the mechanics do not.

Operations must respond without the luxury of pause.

More than that, Operations must do so gracefully. Results are expected. Explanations are required — but not ones that point backward too clearly. Accountability must be demonstrated without appearing to assign blame. And all of it must happen in full view of the audience.

There is no safety net here.

Operations absorbs everyone else’s deferred pressure and holds it indefinitely. It is the place where “we’ll fix it later” finally arrives — and discovers that later has no buffer.

This is why Operations is different.

The pressure comes from every direction: executives who cannot afford failure, builders whose work must function, customers who simply expect reliability, and the system itself demanding equilibrium.

Operations is not where work ends.

It is where work remains.

That reality requires a different DNA — one shaped not by ideation or momentum, but by consequence. In Operations, falling off the tightrope doesn’t just disrupt the show.

It can end it.

The Myth of Later

Most organizations believe in later.

Later is where quality will be added.

Later is where resilience will be addressed.

Later is where known risks will be resolved.

Later allows momentum to continue without confrontation.

At the moment a decision is made, later feels responsible. It acknowledges imperfection without halting progress. It creates psychological closure: the issue has been seen, noted, and deferred.

What is rarely examined is what happens to that decision after it leaves the room.

Later has no owner.

Deferred work does not belong to Operations yet. It cannot be justified as reactive effort because no customer is currently out of service. There is no incident to anchor it to, no outage to defend the spend.

It also does not remain with the build teams. The entire purpose of deferment was to avoid slowing delivery. Once momentum moves on, ownership dissolves.

So the work is pushed into an undefined space — not active enough to demand action, not new enough to command attention.

Later becomes no man’s land.

What fills that vacuum is an unspoken assumption:

if this ever fails, Operations will catch it.

Not because Operations planned to.

But because Operations exists.

This belief changes the nature of the work.

When deferred decisions eventually surface — and they do — they do not return as planned investments. They arrive as incidents. Under pressure. With compressed timelines. And at significantly higher cost.

What was once a design consideration now carries operational premiums:

emergency labor

expedited remediation

customer impact

reputational erosion

The savings once justified by deferment are not preserved. They are amplified in the worst possible way.

Operations inherits not just the work, but its consequences — without the context in which the original trade-offs were made. They are asked to defend spend they did not create, urgency they did not choose, and failures that were structurally inevitable.

This is how deferred work quietly acquires its own unplanned lifecycle.

It affects customers who were never part of the original decision.

It erodes trust that took years to build.

It drags metrics downward long after the launch has been forgotten.

None of this happens because people are careless.

It happens because later was treated as a place, rather than a liability.

Time does not hold deferred work safely. It redistributes it.

What is postponed upstream accumulates downstream. What is deferred strategically resurfaces tactically. What was once optional becomes unavoidable — but under conditions that strip away choice.

Operations does not inherit later as a plan.

It inherits it as reality.

Organizations that mature operationally do not eliminate later. They make it explicit. They bind it to ownership, funding, and revisitation. They recognize that time is not a buffer — it is a multiplier.

Until then, later will continue to function as a comforting fiction.

And Operations will continue to be where it finally collapses.

Ownership Ends at Launch, Accountability Does Not.

Most organizations treat ownership as something that expires.

A product launches.

A system goes live.

A capability is delivered.

At that moment, ownership is considered fulfilled.

What remains is accountability.

This distinction is rarely made explicit, but it shapes nearly every operational failure that follows.

Ownership is exercised upstream. Decisions are made under controlled conditions: timelines are negotiable, trade-offs are debated, assumptions are documented. Authority is present, and options exist.

Accountability, by contrast, emerges downstream. It appears after launch, when the system is live and consequences are no longer theoretical. Options narrow. Time compresses. The work is no longer about design or intent, but outcome.

Operations lives at this boundary.

By the time work arrives in Operations, ownership has already dissolved. The system is no longer being shaped; it is being sustained. Decisions that defined its resilience, scalability, and tolerance for failure have already been made.

Yet accountability remains fully intact.

Operations is judged on availability, performance, and recovery. Metrics are tracked. SLAs are enforced. Customers experience impact in real time. The system does not care who made the original decisions — only that it continues to function.

This creates a structural asymmetry.

Those who exercised authority over design are no longer present when consequences surface. Those who are present when consequences surface lack the authority to change the underlying system.

Accountability without ownership becomes normalized.

This is not the result of malice or neglect. It is a function of how organizations distribute responsibility across time. Ownership is treated as a phase. Accountability is treated as a condition.

The handoff between the two is rarely examined.

Once a system is live, changes become expensive, risky, and politically complex. Preventive decisions that were optional upstream become difficult downstream. What could have been addressed deliberately must now be managed cautiously, under pressure, and often without full context.

Operations is asked to stabilize outcomes it did not design, defend costs it did not create, and explain failures that were structurally embedded long before the incident occurred.

And it must do so without assigning blame.

This is why operational conversations often feel constrained. Root causes are acknowledged carefully. Explanations are framed narrowly. The goal is not to revisit decisions, but to restore equilibrium.

The system rewards containment over correction.

Over time, this reinforces a quiet but persistent pattern: ownership ends at launch, while accountability accumulates indefinitely. Operations becomes the permanent interface between past decisions and present consequences.

Organizations that mature operationally recognize this mismatch.

They extend ownership beyond launch. They bind authority to lifecycle responsibility. They acknowledge that accountability without ownership is not accountability at all — it is exposure.

Until then, Operations will continue to carry responsibility for outcomes it was never empowered to shape.

Not because it failed.

But because it remained.

The Vantage Point Problem in Operations

How pressure distorts judgment, rewrites narratives, and quietly breaks teams

Service was restored in forty-five minutes.

By any operational benchmark, that should have been a win.

Instead, it became the moment a team quietly decided they would never push that hard again.

The outage was labeled self-inflicted. The phrase deserves quotation marks—not because responsibility doesn’t matter, but because in complex infrastructure environments, self-inflicted often means nothing more than being closest to the failure when the system finally gives way.

In this case, the damage occurred at a handhole. The field team was present. The fiber broke. The designation followed automatically.

What mattered less—at least in the official narrative—was that the plant had likely been compromised long before. Deferred quality. Marginal tolerances. Previous work done just well enough to pass. Any one of those can leave infrastructure hanging by a thread. Sometimes, opening the lid is enough.

The team knew how this would be read. And so they moved.

They didn’t slow down.

They didn’t wait for reinforcements.

They didn’t protect themselves.

They restored service in under an hour—an MTTR that typically stretches four to six.

They assumed effort would matter.

They were wrong.

Three Vantage Points. One Incident.

What followed wasn’t chaos. It was something far more predictable.

Everyone involved acted rationally based on the pressure they were under. The failure didn’t come from incompetence or malice. It came from what I’ll call vantage point compression.

Vantage point compression is what happens when pressure collapses perspective—when people stop optimizing for the system and start optimizing for the audience closest to their blast radius.

4

The Field: Where Reality Is Undeniable

From the ground, the situation was clear.

Nothing the team did rose to negligence. The same access methods had been used countless times without incident. There was no reckless act—just fragile infrastructure finally failing.

They also understood the downstream risk.

Once labeled self-inflicted, the incident would climb the escalation chain quickly. Leadership would feel it. The client would feel it. The story would harden before context could catch up.

So they optimized for what they could control: impact.

They reduced customer downtime.

They minimized blast radius.

They protected their leadership from a longer, uglier escalation.

There was no expectation of a bonus. In operations, that’s normal.

What they hoped for—quietly—was acknowledgment. A simple signal that speed mattered. That effort counted. That doing the hard thing under pressure was seen.

Recognition, in operations, isn’t a feel-good gesture.

It’s a performance accelerant.

And its absence is felt immediately.

Leadership: Where Optics Become Currency

The operations VP arrived on site to a very different reality.

Five hundred customers were down.

The outage was self-inflicted.

The escalation chain was already forming.

This leader had been hired for a reason. He came from the client side. He understood expectations. He had been told—explicitly—that it was time to bring discipline, restore confidence, and elevate the organization’s standing.

In that moment, explanation was a liability.

What mattered was signaling:

That the issue was taken seriously

That accountability would follow

That leadership was not “soft”

The audience was not the field team.

It was upstream.

So the response became performative. Voices raised. Consequences implied. Control asserted.

From that vantage point, this wasn’t cruelty.

It was credibility management.

The Client: Where Reassurance Beats Diagnosis

From the client’s perspective, the pattern was wearing thin.

Self-inflicted outages were happening too often. Root causes blurred together. Infrastructure decay was understood—but patience was limited.

When the notification arrived, the first question wasn’t how fast was it fixed?

It was was this preventable?

Once the answer came back as “yes,” what followed was almost automatic.

They needed to see action.

They needed to believe control was being reasserted.

They needed the narrative to stabilize.

Someone had to own the failure—even if the system itself was the real culprit.

Where the System Quietly Breaks

None of this required bad intentions.

Each group optimized for survival within its own pressure envelope. And that is precisely the problem.

When effort is punished under ambiguity, systems don’t become safer.

They become quieter.

The team didn’t revolt.

They didn’t escalate.

They didn’t argue.

They adjusted.

Next time, they would follow procedure exactly.

No extra push.

No personal stretch.

No unrecognized effort.

Compliance would replace care.

The irony is familiar to anyone who’s worked in operations long enough: the people most capable of reducing MTTR and absorbing shock were just taught that initiative carries risk but no upside.

Dashboards may stay green—for a while.

Outages will still be fixed.

But resilience erodes quietly.

And when the system finally fails in ways procedure can’t handle, leadership will wonder where the urgency went.

It didn’t disappear.

It learned.

When Effort Becomes Liability

Why punishment under ambiguity trains teams to do the minimum - and nothing more.

There is a quiet moment in every operations team when something shifts.

No announcement is made.

No policy changes.

No one resigns.

People simply stop stretching.

This moment doesn’t arrive after repeated failures. It usually comes after extraordinary effort is punished.

The Misunderstood Role of Effort in Operations

Operations doesn’t run on heroics. Everyone knows that—or says they do.

But it also doesn’t run on compliance alone.

What keeps complex systems stable isn’t procedure. It’s discretion:

Knowing when to push

When to bend

When to absorb shock personally so the system doesn’t have to

That discretionary effort is never written down.

And it is never guaranteed.

It’s offered conditionally.

The Unwritten Contract

Most operations teams operate under an unspoken agreement:

If we stretch when it matters, the system will recognize that difference.

Not with bonuses.

Not with praise every time.

But with fairness.

When that contract is broken—especially in moments where causality is murky—the response is not rebellion.

It’s withdrawal.

Punishment Under Ambiguity

Ambiguity is unavoidable in real systems.

Infrastructure degrades unevenly.

Failures inherit history.

Root causes blur across time, teams, and vendors.

When leadership responds to ambiguous outcomes with certainty and punishment, the lesson learned is not accountability.

The lesson is risk avoidance.

And risk avoidance has a predictable behavioral output:

Do exactly what is required. Nothing more.

4

Why Compliance Is So Appealing (and So Dangerous)

Compliance feels safe to leadership.

It’s measurable

It’s defensible

It looks disciplined

But compliance is a lagging indicator of system health.

A team that only complies will:

Follow process even when it’s clearly insufficient

Escalate early to protect themselves

Avoid initiative when outcomes are uncertain

Not because they don’t care—but because they’ve learned what caring costs.

The False Tradeoff: Discipline vs Resilience

Many organizations believe they must choose:

Either enforce discipline

Or tolerate mistakes

This is a false binary.

The real distinction is between:

Negligence, which deserves correction

Ambiguity, which demands learning

When those two are treated the same, resilience collapses quietly.

Teams don’t stop showing up.

They stop thinking.

What Gets Lost When Effort Is Trained Out

The loss isn’t immediate.

MTTR may hold—for a while.

Dashboards may remain green.

Escalations may even decrease.

What disappears first is judgment.

Then ownership.

Then initiative.

By the time leadership notices, the system has already hardened into something brittle—incapable of absorbing shock without breaking.

The Quietest Failure Mode

There is no alert for this.

No Sev 1.

No bridge call.

No postmortem.

Just a steady drift toward minimum viable performance.

And when the next crisis arrives—one that procedure alone cannot solve—leaders will ask the wrong question:

“Why didn’t anyone step up?”

The answer is uncomfortable, but consistent:

They did.

Once.

And they learned.